“I believe the intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups. . . .” So wrote the British physicist and novelist C. P. Snow in his famous The Two Cultures Rede Lecture delivered at Cambridge University in 1959. Although Snow was mostly concerned with the divisions he felt in his own personal and professional experience between the “literary intellectuals” and “physical scientists,” the two-culture split has come to symbolize a wider and ever-growing gulf in academia between the sciences and the humanities. This split, and the strife it often generates, is palpable in most universities, and it speaks directly to the heart of the liberal arts curriculum of schools across the globe, and to the markedly wrong, widespread perception that in a technology-driven world, the humanities are an anachronism.

The roots of this unfortunate split between...

As influential thinkers promoted science as the sole source of truth, the humanities lost some of their clout, and the rift between the two cultures gained momentum. “Literary intellectuals at one pole—at the other scientists, and as the most representative, the physical scientists. Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension—sometimes (particularly among the young) hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding,” wrote Snow. Experts hid behind the jargons of their respective fields and either talked past each other, or worse, didn’t talk to each other at all. The frontiers of knowledge broadened, academic departments multiplied, and with them, the walls separating experts in ever narrower subdisciplines.

Perhaps the greatest virtue of Snow’s essay was to describe science as a culture. And that it surely is, both within its practices and practitioners and as a driver of profound changes in humanity’s collective worldview since the seventeenth century. The relentless ascent of scientific thinking brought the contempt of many humanists who considered themselves as the only worthy intellectuals—scientists are technicians; humanists are intellectuals. Ensconced within their turf, most scientists returned the disdain, considering the humanities to be worthless for their intellectual pursuits. “Philosophy is useless,” well-known scientists have proclaimed. “Religion is dead.”

See “Opinion: Bridging the Intellectual Divide ”

We can see the tension—and the issues it creates—most clearly in areas where science encroaches upon territory that has historically been chartered primarily by humanists. It is common to hear that science is about nature, while the humanities deal with values, virtue, morality, subjectivity, and aesthetics; hard to quantify concepts about which science has nothing or very little to say. To describe love as a set of biochemical reactions taking place due to the flow of a handful of neurotransmitters through certain regions of the brain is clearly important, but it does very little to describe what the experience of being in love feels like.

Such polarizations are deeply simplistic and are growing less relevant every day. Current developments in the physical, biological, and neuro- sciences deem such narrow-minded antagonism and mutual exclusion as problematic and downright corrosive. It limits progress and inhibits creativity. Many of the key issues of our times, an illustrative sample being the questions explored in this volume, call for a constructive engagement between the two cultures. It is our contention that the split between the sciences and the humanities is largely illusory and unnecessary, in need of a new integrative approach. We need to reach beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries to create truly cross-disciplinary ways of thinking. It is no longer enough to read Homer and Einstein or Milton and Newton as disjoint efforts to explore the complexities of the world and of human nature. The new mindset proposes that the complexities of the world are an intrinsic aspect of human nature as we experience reality. We cannot separate ourselves from a world that we are a part of. Any description or representation, any feeling or interpretation, is a manifestation of this embedding. Who we are and what we are form an irreducible whole.

The questions that call for an engagement between the sciences and the humanities are not restricted to academia. Consider the future of humanity in an ailing planet as we move toward a more thorough hybridization with machines. We currently extend our physical existence in space and time through our cell phones, while many scientists and humanists consider futuristic scenarios where we will transcend the body, becoming part human and part machine, with some even speculating that a singularity point will be reached when machines will become smarter than we are—although they are rather vague on the meaning of smarter. Such technological advances call into question the wisdom of our scientific advances, raising issues related to machine control, the ethics of manipulating humans and other lifeforms, the impact of robotization and artificial intelligence in the job market and in society, and our predatory relationship with our home planet. There is a new culture emerging, inspired by questions old and new that reside at the very core of our pursuit of knowledge. The choices we make now, as we shape our curricula and create academic departments and institutes and engage in discussions with the general public, will shape generations and the nature of intellectual cooperation for decades to come.

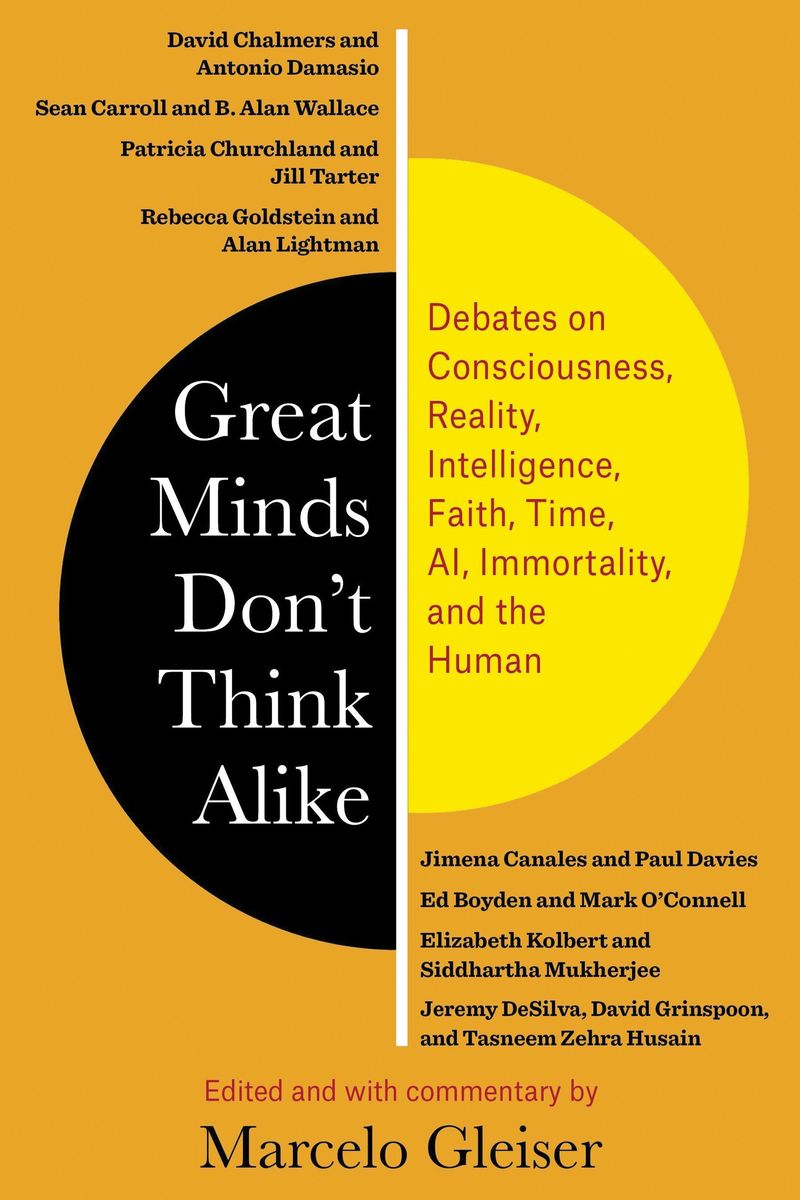

Excerpted from Great Minds Don't Think Alike, edited and with commentary by Marcelo Gleiser. Copyright © 2021 Columbia University Press.

Interested in reading more?