YURI WOLFAs a middle school student in Moscow, Russia, Eugene Koonin read the work of pioneering scientists such as Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling, who together in 1962 founded the field of molecular evolution through a prescient analysis of just a few snippets of protein sequences. “I had the good fortune to read these papers quite early,” he says. “I just thought that this was the right way to study life, although at the time . . . the available data were completely inadequate.” Koonin completed a PhD at Moscow State University, where he investigated the replication mechanisms of RNA viruses. “This introduced me to the world of viruses and other mobile genetic elements that remains incredibly fascinating to this day,” he says. While working at the Institutes of Poliomyelitis and Microbiology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, Koonin began to apply computational tools to unravel microbial evolution....

YURI WOLFAs a middle school student in Moscow, Russia, Eugene Koonin read the work of pioneering scientists such as Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling, who together in 1962 founded the field of molecular evolution through a prescient analysis of just a few snippets of protein sequences. “I had the good fortune to read these papers quite early,” he says. “I just thought that this was the right way to study life, although at the time . . . the available data were completely inadequate.” Koonin completed a PhD at Moscow State University, where he investigated the replication mechanisms of RNA viruses. “This introduced me to the world of viruses and other mobile genetic elements that remains incredibly fascinating to this day,” he says. While working at the Institutes of Poliomyelitis and Microbiology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, Koonin began to apply computational tools to unravel microbial evolution....

COURTESY OF MART KRUPOVICA single microbiology lecture at Vilnius University sparked Mart Krupovic’s attraction to viruses and his desire to study their origins. He pursued a PhD with Dennis Bamford at the University of Helsinki in Finland, where he studied the molecular underpinnings of virus-host interactions and worked on characterizing viral diversity. “All of these things are equally exciting for me, but I always try to look at them from an evolutionary perspective,” he says. As a research scientist in the Molecular Biology of the Gene in Extremophiles unit at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, he is examining other mobile genetic elements, “trying to see what part viruses occupy within this gigantic mobilome.” During a three-month stint in Koonin’s lab in early 2014, Krupovic and Koonin discovered a transposon origin for a component of bacterial and archaeal CRISPR-Cas antiviral defense systems.

COURTESY OF MART KRUPOVICA single microbiology lecture at Vilnius University sparked Mart Krupovic’s attraction to viruses and his desire to study their origins. He pursued a PhD with Dennis Bamford at the University of Helsinki in Finland, where he studied the molecular underpinnings of virus-host interactions and worked on characterizing viral diversity. “All of these things are equally exciting for me, but I always try to look at them from an evolutionary perspective,” he says. As a research scientist in the Molecular Biology of the Gene in Extremophiles unit at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, he is examining other mobile genetic elements, “trying to see what part viruses occupy within this gigantic mobilome.” During a three-month stint in Koonin’s lab in early 2014, Krupovic and Koonin discovered a transposon origin for a component of bacterial and archaeal CRISPR-Cas antiviral defense systems.

In their feature, “A Movable Defense,” Koonin and Krupovic detail this finding and the involvement of other genetic transfers in the evolution of immune defense.

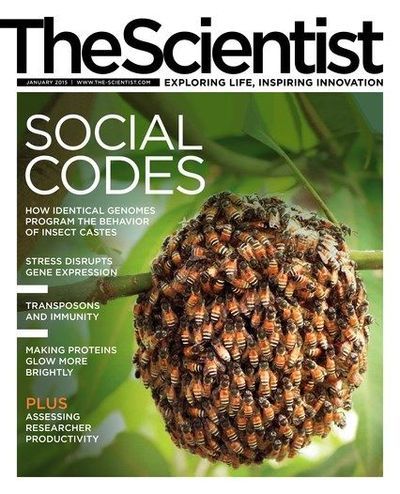

COURTESY OF SEIRIAN SUMNERSeirian Sumner studied the behavior of Malaysian wasps as a PhD student at University College London (See “Seirian Sumner: Wasp Whisperer,” The Scientist, August 2011). “I found myself lying on the floor of the rainforest, with a wasp nest a few centimeters from my face, yelling out the colour codes that we’d painted our wasps with,” she writes in an e-mail describing her first field season. “I was covered in mud, who knows how many creepy crawlies, and suddenly realised what a peculiar thing I’d got myself into!” As a research fellow at London’s Institute of Zoology, Sumner continued to explore the molecular foundations of social behavior in wasps and other insects and cofounded Soapbox Science, an annual public-outreach event focused on female scientists. Now a senior lecturer in behavioral biology at the University of Bristol, she is thrilled by the capabilities of next-generation sequencing to take the field of sociogenomics far beyond the honeybee.

COURTESY OF SEIRIAN SUMNERSeirian Sumner studied the behavior of Malaysian wasps as a PhD student at University College London (See “Seirian Sumner: Wasp Whisperer,” The Scientist, August 2011). “I found myself lying on the floor of the rainforest, with a wasp nest a few centimeters from my face, yelling out the colour codes that we’d painted our wasps with,” she writes in an e-mail describing her first field season. “I was covered in mud, who knows how many creepy crawlies, and suddenly realised what a peculiar thing I’d got myself into!” As a research fellow at London’s Institute of Zoology, Sumner continued to explore the molecular foundations of social behavior in wasps and other insects and cofounded Soapbox Science, an annual public-outreach event focused on female scientists. Now a senior lecturer in behavioral biology at the University of Bristol, she is thrilled by the capabilities of next-generation sequencing to take the field of sociogenomics far beyond the honeybee.

LYNNE SHONEWhile in high school in Berkshire, England, Claire Asher “fell in love with the logic” of biology, and later became fascinated by cooperative behavior in animals. Asher earned a PhD from the University of Leeds, where she investigated the social structure of the Brazilian dinosaur ant Dinoponera quadriceps. Working with Sumner and William Hughes (now at the University of Sussex), she showed that “high-ranking workers—the ones that have a chance of taking over the colony—basically don’t do any work, and they certainly don’t do any of the difficult or dangerous jobs in the colony.” This finding seems “eerily reminiscent of humans,” Asher says. She also performed transcriptome sequencing on ants of different behavioral castes to analyze the genetic bases of their roles. In the midst of her graduate studies, Asher created a science blog, Curious Meerkat, and she now works as a freelance writer and a knowledge-transfer specialist in the Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research at University College London.

LYNNE SHONEWhile in high school in Berkshire, England, Claire Asher “fell in love with the logic” of biology, and later became fascinated by cooperative behavior in animals. Asher earned a PhD from the University of Leeds, where she investigated the social structure of the Brazilian dinosaur ant Dinoponera quadriceps. Working with Sumner and William Hughes (now at the University of Sussex), she showed that “high-ranking workers—the ones that have a chance of taking over the colony—basically don’t do any work, and they certainly don’t do any of the difficult or dangerous jobs in the colony.” This finding seems “eerily reminiscent of humans,” Asher says. She also performed transcriptome sequencing on ants of different behavioral castes to analyze the genetic bases of their roles. In the midst of her graduate studies, Asher created a science blog, Curious Meerkat, and she now works as a freelance writer and a knowledge-transfer specialist in the Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research at University College London.

Sumner and Asher describe how omics techniques are transforming researchers’ views of eusocial insects in “The Genetics of Society.”

Interested in reading more?